What are the protein needs of the elderly?

31 July 2019

There are some complications due to age. One of these is the muscular mass loss which can significantly affect quality of life by limiting mobility.

From what age do we consider these muscle problems?

Overall, there are three age categories to define:

- The middle-age, i.e. people between 40 and 65 years old. Muscular loss is still minimal and it is especially important to act PREVENTIVELY;

- The pre-elderly between 65 and 75 years old. Certain muscular problems can occur and the goal will be to PREVENT and TREAT them ;

- The elderly, which are over the age of 75. Muscular problems are more important. More age-related diseases can take a hold but it is still possible to TREAT them.

The aim is then to determine how the lifestyle modification can prevent and limit muscular diseases development due to age.

How do these age-related complications occur?

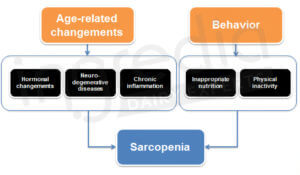

As from the age of 40 to 50 years old, a reduction of muscular mass and physical abilities begins to appear. It represents a loss from 3 to 8% of muscular mass every 10 years depending on the lifestyle1 2. This is the potential beginning of sarcopenia, i.e. the age-related muscular mass loss which is a multifactorial disease (figure 1) 3.

Figure 1: Main causes of sarcopenia

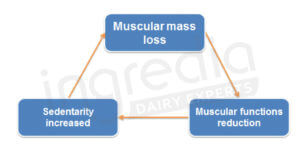

It is essential to react as soon as possible to avoid falling into the vicious circle of sarcopenia (figure 2). In order to do this, we can act on the behavioral causes (figure 1), especially on nutrition and physical activity 3.

Figure 2: The ‘vicious circle’ of sarcopenia

Can we act through a diet modification?

Yes, we can. The following recommendations allow prevention and treatment of age-related muscular troubles (like sarcopenia). These must be followed from middle-age on.

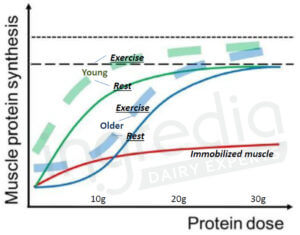

In order to stimulate anabolism* of old muscle, an increased protein dose is necessary in comparison to younger muscles. A 2012 study has shown that a small quantity of about 5g of proteins was sufficient to trigger anabolism for young adults. A maximal answer was observed from approximately 20g. While for elderly, a quantity twice as important was needed for the same results (i.e. between 30 and 40g for a maximal answer, as shown in the figure 3) 4 5 6 7. This phenomenon has also been shown during a 2015 meta-analysis: the protein amount necessary to contribute to an optimal anabolism is 0.24g/kg of the bodyweight per meal for the young people and 0.40g/kg for the elderly 8. Hence the importance of increasing the protein intake for the elderly.

Figure 3: Muscular protein synthesis in function of the ingested protein dose for the young people (green curves) and the elderly (blue curves) 4 .

The full curves correspond to anabolism observed for muscle at rest, and the dotted curves for muscle after a physical activity.

The most important point is to provide enough proteins to the body in order to increase the muscular protein synthesis. 1.2g of proteins per kilogram of the bodyweight per day is a minimum to maintain muscular mass and improve physical abilities 2 9 10. Certain studies show that it would even be useful to consume a protein amount up to 1.5g/kg/d to ensure an efficient maintenance of muscular functions 11 12 13. However protein intake recommendations at the adulthood are 0.8g/kg/d. Then, the aim would be to double these daily recommendations. So it can be hard to consume that many proteins especially if the appetite decreases. That is the reason why protein supplements can represent a good alternative to cover protein needs in the case of malnutrition under medical supervision5.

Is it really necessary for elderly to consume that much protein?

Yes, it is. We often imagine that a high protein diet can cause kidney complications. However, no study currently shows that a high protein diet will create this kind of problems in healthy people 14. Nevertheless, a high protein diet is not recommended for people with known kidney problems or predispositions. In this case, protein consumption higher than 0.8g/kg/d can be harmful for certain people 15.

Is protein alone enough or is physical activity necessary?

Physical activity is the stimulus which enhances muscular protein synthesis. The figure 4 comes from a study of 2013 which compare anabolism depending on the ingested protein dose (whey in this study) and the physical activity. We can note that exercise allows a significant increase of the anabolism level 16.

Figure 4: Muscular protein synthesis depending on the amount of protein ingested and the physical activity13.

The Myofibrillar FSR (Fractional Synthetic Rate) corresponds to the anabolism rate.

Most researches seem to indicate that a protein supplementation without exercise does not allow a sustainable muscular mass increase of the elderly 3 17. Therefore, protein supplementation alone seems to be insufficient. This led the World Health Organization to recommend that people over 65 years old do at least 150 minutes of endurance activity at a moderate intensity, or 75 minutes at high intensity each week. It is also advised to do muscle strengthening exercises at least twice a week18.

We talk a lot about proteins, but are they the only nutrients to bring in greater quantities?

No, they are not. Micronutrients are also important, especially calcium and vitamin D. An adequate intake of these contributes to the muscular mass and strength maintenance. Moreover calcium and vitamin D are essential to ensure bone capital maintenance 19.

First, let us review about the bone capital: there is a mechanism of turnover similar to the protein one. Overall, until the age of about 50, bone density stay constant because of the balance between synthesis and degradation. However, after 50 years old, degradation can exceed synthesis. Then bone density reduction can occur. A lack of treatment can lead to osteoporosis. Bones become porous and brittle, increasing the risk of fracture. If we add a potential muscular mass and strength reduction caused by sarcopenia, then we have a consequent increase of serious falls. This can lead to major mobility problems 20.

An increase in vitamin D and calcium consumption can ensure a better maintenance of its bone and muscular capital. But under-consumption of vitamin D is frequent: recommended daily intakes provided by the ANSES (French agency of food safety) are 15µg for adults. However, the average consumption is about 3.1µg/d in France, which is 5 times lower than ANSES recommendations! So it is necessary to provide more vitamin D in order to fill that potential gap 21.

For calcium, it is recommended to consume between 900 and 1200mg per day for people over 50 years old. The average daily consumption is sufficient but not excessive since it is about 900mg. Therefore it is important to make sure that the diet is sufficiently rich in calcium 22.

Alright, then what food should we eat?

It is a very valid question because all proteins are not equivalent. It is necessary to choose a source of good quality proteins corresponding to our needs. And this will be the topic of the next article. It will detail the interest of milk proteins to prevent sarcopenia.

For more information on our milk proteins and our expertise, contact us.

Authors: Rémi Maleterre & Audrey Boulier.

* [Anabolism] : Muscular protein synthesis.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Paddon-Jones D., Leidy H. (2014). Dietary protein and muscle in older persons. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care vol. 17, 1:5-11. Epub September 12, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0000000000000011

[2] Marzetti E., Calvani R., Tosato M., Cessari M., Di Bari M., Cherubini A., Collamati A., D’Angela E., Pahor M., Bernabel R., Landi F. (2017). « Sarcopenia: An Overview ». Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, vol. 29, no 1, p. 11‑17. Epub February 2, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-016-0704-5

[3] Cruz-Jentoft A.J., Bahat G., Bauer J., Boirie Y., Bruyère O., Cerderholm T., Cooper C., Landi F., Rolland Y., Sayer A.A., Schneider S.M., Sieber C.C., Topinkova E., Vandewoude M., Visser M., Zamboni M. (2018). Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 39(4): p. 412-23. Epub January 01, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169

[4] D. Dardevet, D. Rémond, M.A. Peyron, I. Papet, I. Savary-Auzeloux, L. Mosoni (2012). Muscle wasting and resistance of muscle anabolisme : the « anabolic threshold concept » for adapted nutritional strategies during sarcopenia. The Scientific World Journal, Vol 2012, ID 269531. Epub December 03, 2012. https://dx.doi.org/10.1100/2012/269531

[5] K. Dideriksen, S. Reitelseder, L. Holm (2013). Influence of amino acids dietary protein and physical activity on muscle mass development in humans. Nutrients 2013, 5(3), 852-876. Epubl March 13, 2013. https://doi.or/10.3390/nu5030852

[6] D. Tomé (2018 – Lille, France) – Protein Digestibility Scores & Nutrition, AgroParisTech – Departement of Life Sciences and Health; INRA, UMR Nutrition physiology and ingestive behavior.

[7] Moore DR, Robinson MJ, Fry JL, Tang JE, Glover EI, Wilkinson SB, Prior T, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM. Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(1):161–8.

[8] Moore DR, Churchward-Venne TA, Witard O, Breen L, Burd NA, Tipton KD, Phillips SM. Protein ingestion to stimulate myofibrillar protein synthesis requires greater relative protein intakes in healthy older versus younger men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015;70(1):57–62.

[9] Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM, Zúñiga C, Arai H, Boirie Y, Chen LK, Fielding RA, Martin FC, Michel JP, Sieber C, Stout JR, Studenski SA, Vellas B, Woo J, Zamboni M, Cederholm T (2014) Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing 43:748–759. doi:10.1093/ageing/afu115

[10] Traylor D.A., Gorissen S.HM, Phllips S.M. (2018). Perspective: protein requirements and optimal intakes in aging: are we ready to recommend more than the recommended daily allowance? Advances in Nutrition, Volume 9, Issue 3, Pages 171–182. Epub May 15, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy003

[11] Murphy CH, Saddler NI, Devries MC, McGlory C, Baker SK, Phillips SM. Leucine supplementation enhances integrative myofibrillar protein synthesis in free-living older men consuming lower- and higher-protein diets: a parallel-group crossover study. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;104(6):1594–606

[12] Kim IY, Schutzler S, Schrader A, Spencer H, Kortebein P, Deutz NE, Wolfe RR, Ferrando AA. Quantity of dietary protein intake, but not pattern of intake, affects net protein balance primarily through differences in protein synthesis in older adults. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2015;308(1):E21–8.

[13] Mitchell CJ, Milan AM, Mitchell SM, Zeng N, Ramzan F, Sharma P, Knowles SO, Roy NC, Sjodin A, Wagner KH, et al. The effects of dietary protein intake on appendicular lean mass and muscle function in elderly men: a 10-wk randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106(6):1375–83.

[14] M. Cuenca-Sánchez, D. Navas-Carrillo, E. Orenes-Piñero (2015). Controversies Surrounding High-Protein Diet Intake: Satiating Effect and Kidney and Bone Health, Advances in Nutrition, Volume 6, Issue 3, May 2015, Pages 260–266. Epub May 2015. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.114.007716

[15] M.C. Huang, M.E Chen, H.C. Hung, H.C. Chen, W.T. Chang, C.H. Lee, Y.Y. Wu, H.C. Chiang, S.J. Hwang (2008). Inadequate energy and excess protein intakes may be associated with worsening renal function in chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr 2008;18:187–94. Epub March 2008. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2007.08.003

[16] O.C. Witard, S.R. Jackman, L. Breen, K. Smith, A. Selby, K.D. Tipton (2014). Myofibrillar muscle protein synthesis rates subsequent to a meal in response to increasing doses of whey protein at rest and after resistance exercise, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 99, Issue 1, Pages 86–95. Pub January 2014. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.055517

[17] Tieland M, van de Rest O, Dirks ML et al. Protein supplementation improves physical performance in frail elderly people: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012b; 13: 720–6. Epub October 2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.07.005

[18] OMS (Organisation Mondiale de la Santé), « L’activité physique des personnes âgées » [consulté le 01 juillet 2019]. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_olderadults/fr/

[19] B. Hamilton (2010). Vitamin D and Human Skeletal Muscle. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 20:182-190. E pub July 8, 2019. https://doi.or/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01016.x

[20] J.A. Kanis, L.J. Melton, C. Christiansen, C.C. Johnston, N. Khaltaev (1994). The diagnosis of osteoporosis. Journal of bone and mineral research. Vol 9:8. Pub August 1994. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.5650090802

[21] National agency of food safety, environment and work (ANSES). (2019) Vitamine D: presentation, besoins nutritionnels et sources alimentaires. At : https://www.anses.fr/fr/content/vitamine-d

[22] National agency of food safety, environment and work (ANSES). (2019) Le Calcium: presentation, sources alimentaires et besoins nutritionnels. At : https://www.anses.fr/fr/content/le-calcium